Loading...

Polystyrene, glass.

34 cm x Ø 34 cm / 13 3/8 x Ø 13/8 in.

VB_2016_11_24

Polystyrene, glass.

Ø 71 x 13,5 cm / Ø 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique

Polystyrene, quartz.

33 x 38 x 20 cm / 13 x 15 x 7 3/4 in.

VB_2016_09_11

Polystyrene, glass.

30 x 32 x 22 cm / 11 3/4 x 12 1/2 x 8 1/2 in.

INV N° VB_2016_09_30

Polystyrene, glass.

Ø 71 x 13,5 cm / Ø 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique

Polystyrene, glass.

Ø 71 x 13,5 cm / Ø 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique

Polystyrene, glass.

Ø 71 x 13,5 cm / Ø 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique

VB_2016_10_07

Polystyrene, glass.

Ø 71 x 13,5 cm / Ø 28 x 5 1/4 in.

VB_2016_10_06

Composite materials, copper.

5 m x Ø 3,40 m / 16 ft 4 3/4 x Ø 11 ft 1 3/4 in.

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

5 m x Ø 3,40 m / 16 ft 4 3/4 x Ø 11 ft 1 3/4 in

Unique

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

5 m x Ø 3,40 m / 16 ft 4 3/4 x Ø 11 ft 1 3/4 in

Unique

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Composite materials, copper.

5 m x Ø 3,40 m / 16 ft 4 3/4 x Ø 11 ft 1 3/4 in.

Unique

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Tree of Life

Gowri Balasegaram

2016

"Inside and outside are inseparable. The world is wholly inside and I am wholly outside myself"

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception.

In this enigmatic statement the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty sums up his thoughts on perception. For the phenomenologist, seeing is not a passive action but a kind of 'creative receptivity' where the perceiving subject and the perceived object exist in a dialectical relationship. Merleau-Ponty is also enthralled by the manner in which artists see things, believing that they possess a 'primal vision' that exists beyond their personal subjectivities. He wrote of the sensation of being in the 'presence' of an object, citing Paul Cézanne the post-impressionist artist who observed: "I have felt many times over it was not I who looked at the forest. Some days I felt that the trees were looking at me." Merleau-Ponty describes the artist's vision as a movement that both extends the body through the act of looking and opens the body to the world through this extension. The body sees and is seen. The artist unveils the object, while at the same time the object reveals itself to him. Merleau-Ponty's thoughts on perception have remained as prescient today as they were then, and have influenced ground-breaking sculptors like Bruce Nauman and Robert Morris.

One of the first impressions of Vincent Beaurin's Tree of Life is that sensation of being in the 'presence' of something, which Merleau-Ponty wrote of. Like the African baobab tree which lends it's name to the sculpture, it is vital almost animate. Rising from a low bed of wild grass, the structure comprises a base, tumescent and weighty like a tree trunk, which tapers to form a conical end, out of which emerge three identical arms delicately arched upwards to form three heads. The deep bronze colour of the copper patina is reminiscent of the earth of the African Masaai region, and its matt surface is unreflecting of the blazing light and coruscating heat of the Tropics. It is seemingly -although deceptively- inured to its surrounding; it is at once autonomous from its environment and wholly part of it too.

The mutual awareness between the body and the object, or the seer and the seen, points to a notion of sculpture as a performance between the work and the viewer. Walking around an object, one perceives different impressions which flow into one another as the object reveals itself like an elaborate dance. With Tree of Life it is apparent that the impressions vary enormously. From a tree to the rudder of an inverted torpedo, to a three-headed hydra, to the stamen of the flower, or the ventricle of a heart, or a petal as it unfolds to the sun, these associations flow stealthily from one to another. The overall feeling is one of gradual flux, of graceful movement and of natural undulations, of precision and of geometry. Tree of Life is forever becoming.

This eluding of classification is a characteristic that underpins the sculpture's formal qualities, which manifest themselves as paradoxes: it appears turgid, yet is hollow; it appears impervious to the elements, yet is porous; it appears weighty, yet is light. The sensation of touching its surface is not one of hardness or density, as one might expect, but smoothness, not dissimilar to that of a leathered 'skin'. It is a sculpture located in a private residence, yet it is visible from the street putting it almost in the public realm. It is neither representational nor is it abstract.

These idiosyncratic qualities can be attributed to the materiality of the sculpture. Epoxy resin, cork, carbon and glass fibres make up the core of the structure, which is then exposed to a rigorous copper coating process derived from that used by specialist boat makers to hinder the development of marine growth on the hull of boats. Here Beaurin inverts the process thus enabling the copper surface to react with the elements, in particular rainwater, so plentiful and predominant in this region. It is this process that both imbues the sculpture with its particular hue and renders it susceptible to the vicissitudes of the elements. Beaurin first trialled this technique on his feted sea sculpture Arch, created for Cheval Blanc Randheli in the Maldives. With the passing of time the oxidised copper will yield a layer of sediment, the colour of the patina will darken, and like skin will be marked by the ageing process. Now, only a few months after its installation, the colour of the patina is lightly modulated in places, making Tree of Life more akin to a living organism.

It is fitting that Tree of Life as a record of time or memory stands opposite an arch marking the main entrance of a house, the place of intimacy and memory. Indeed one has to pass Tree of Life, either partially in a 45 degree angle or walk almost completely around it in order to enter the house, and as such the work is a continuum of the threshold of the house. By extension, it is a place where inside and outside meet. Gaston Bachelard in his book The Poetics of Space defines outside space as immensity and inside space as intimacy. For Bachelard, the union of intimacy and immensity yields intensity or concentration of being. Being located in the space of that union and intensity must only serve to augment the sculpture's sense of presence.

This interplay between inside and outside space is another example of the many paradoxes that inhabit the formal qualities of the work. There is a harmonious exchange or reconciliation between the negative space within the hollow sculpture and the open space of the sculpture's three arms; its body appears dense with no space inside, whilst the space within its clasp appears to be immanent with the sculpture. It calls to mind Vincent Beaurin?s own thoughts on art: "The pertinence of art is not how a thing conforms to the eye but in the resolution of the contradictions and confusion which the act of looking generates. I am a sculptor. I create devices to bring about this sort of reconciliation."

Gowri Balasegaram is an art critic, and a curator, based in Kuala Lumpur.

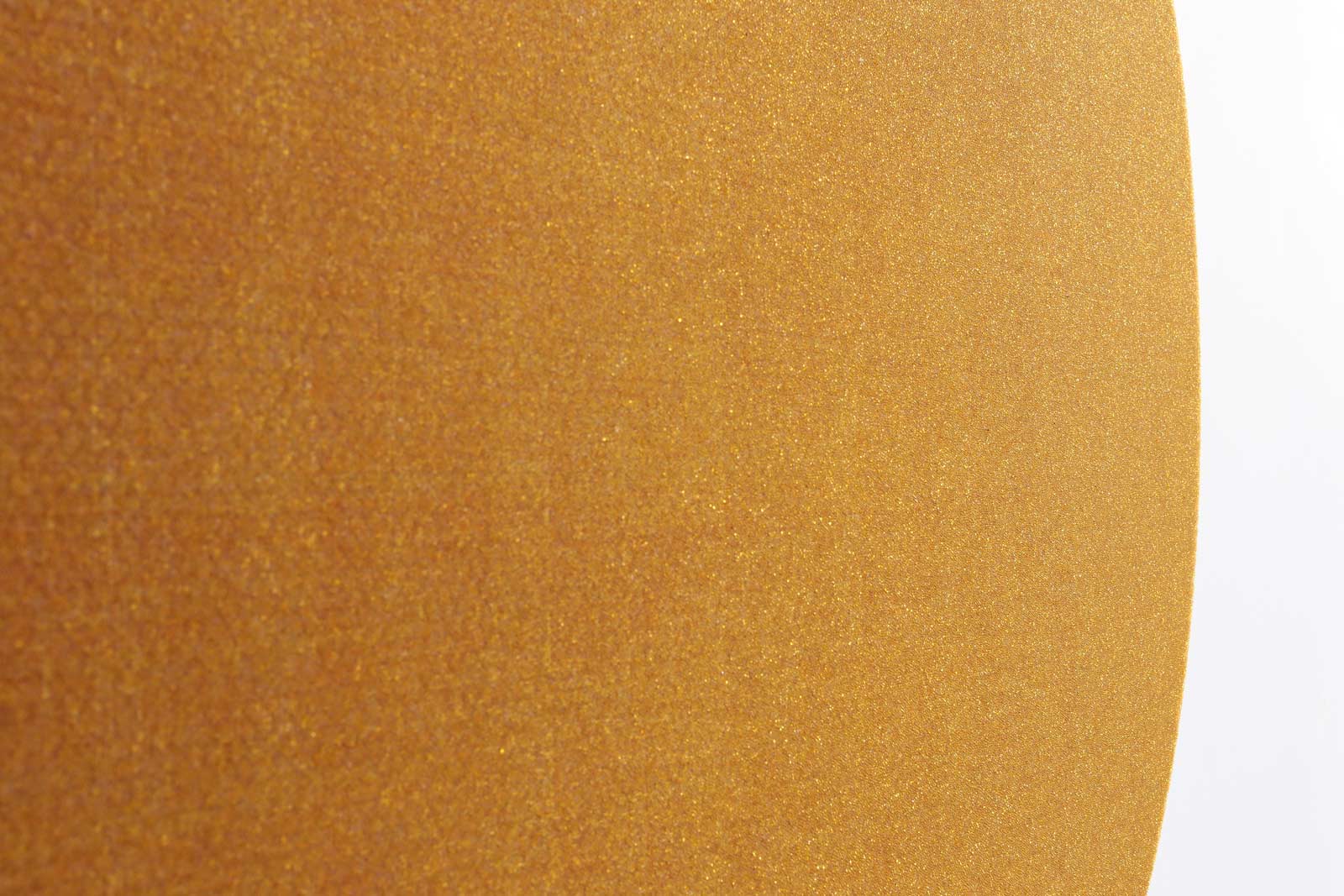

Composite material, glass.

115 x 166,5 x 2,5 cm / 45 1/4 x 65 1/2 x 1 in.

Unique

Detail

Composite material, glass.

115 x 166,5 x 2,8 cm / 45 1/4 x 65 1/2 x 1 in.

Unique