Loading...

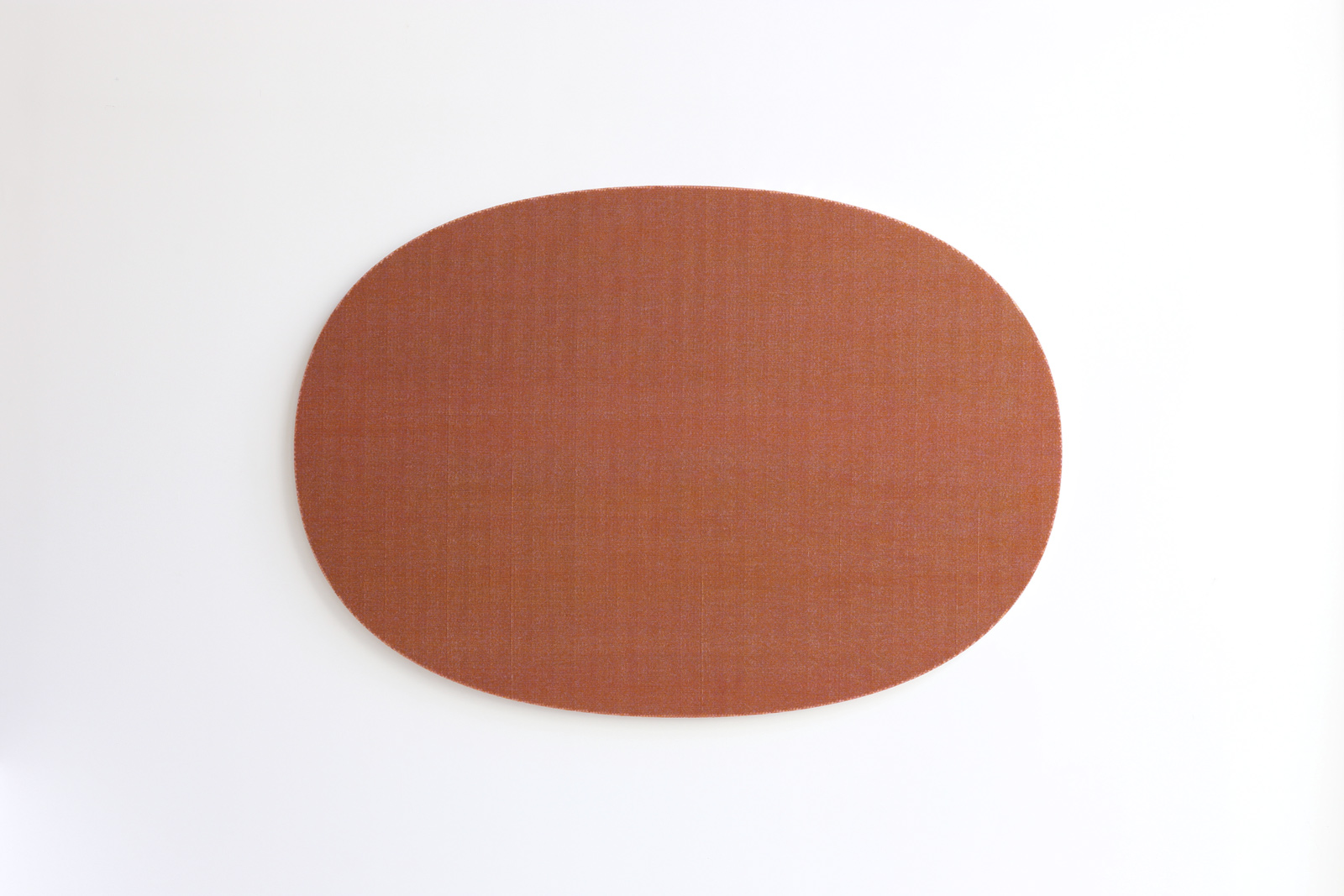

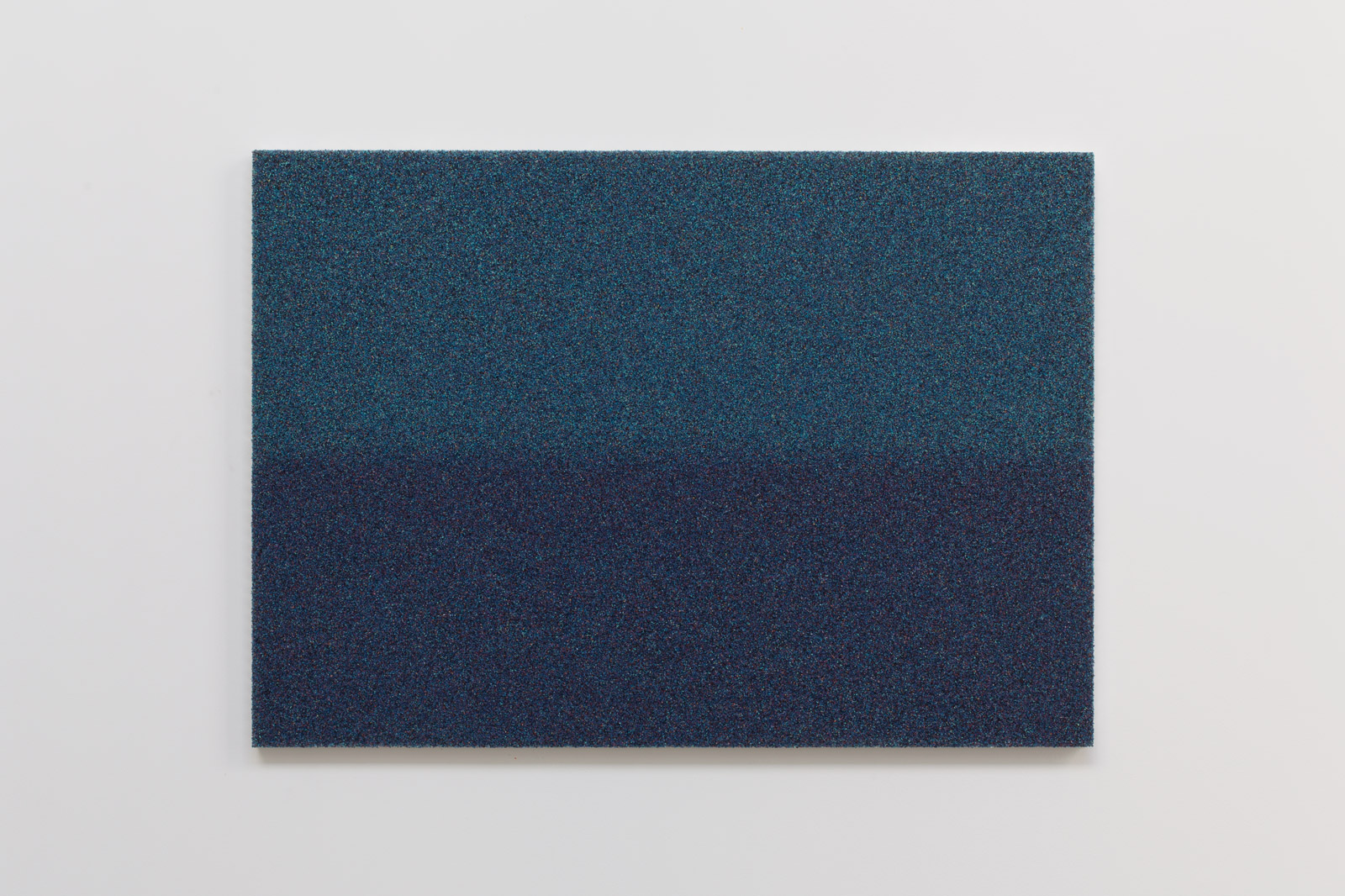

Composite material, glass.

115 x 166,5 x 2,5 cm / 45 1/4 x 65 1/2 x 1 in.

VB_2016_08_17

Detail

Composite material, glass.

115 x 166,5 x 2,8 cm / 45 1/4 x 65 1/2 x 1 in.

Unique

Matériaux composites, cuivre.

4,20 x 5,55 x 3,50 m / 14 ft x 18 ft 2 in. x 11 ft 6 in.

Unique

Cheval Blanc Randheli collection, Noonu atoll, Maldives.

Composite materials, copper.

4,20 x 5,55 x 3,50 m / 14 ft x 18 ft 2 in. x 11 ft 6 in.

Unique

Cheval Blanc Randheli collection, Noonu atoll, Maldives.

4,20 x 5,55 x 3,50 m

Unique

Cheval Blanc Randheli collection, Noonu atoll, Maldives.

4,20 x 5,55 x 3,50 m

Unique

Cheval Blanc Randheli collection, Noonu atoll, Maldives.

Detail

Composite materials, copper.

420 x 555 x 350 cm / 165 x 218 x 138 in.

Unique

Commissioned by Cheval Blanc Randheli, Maldives, LVMH group.

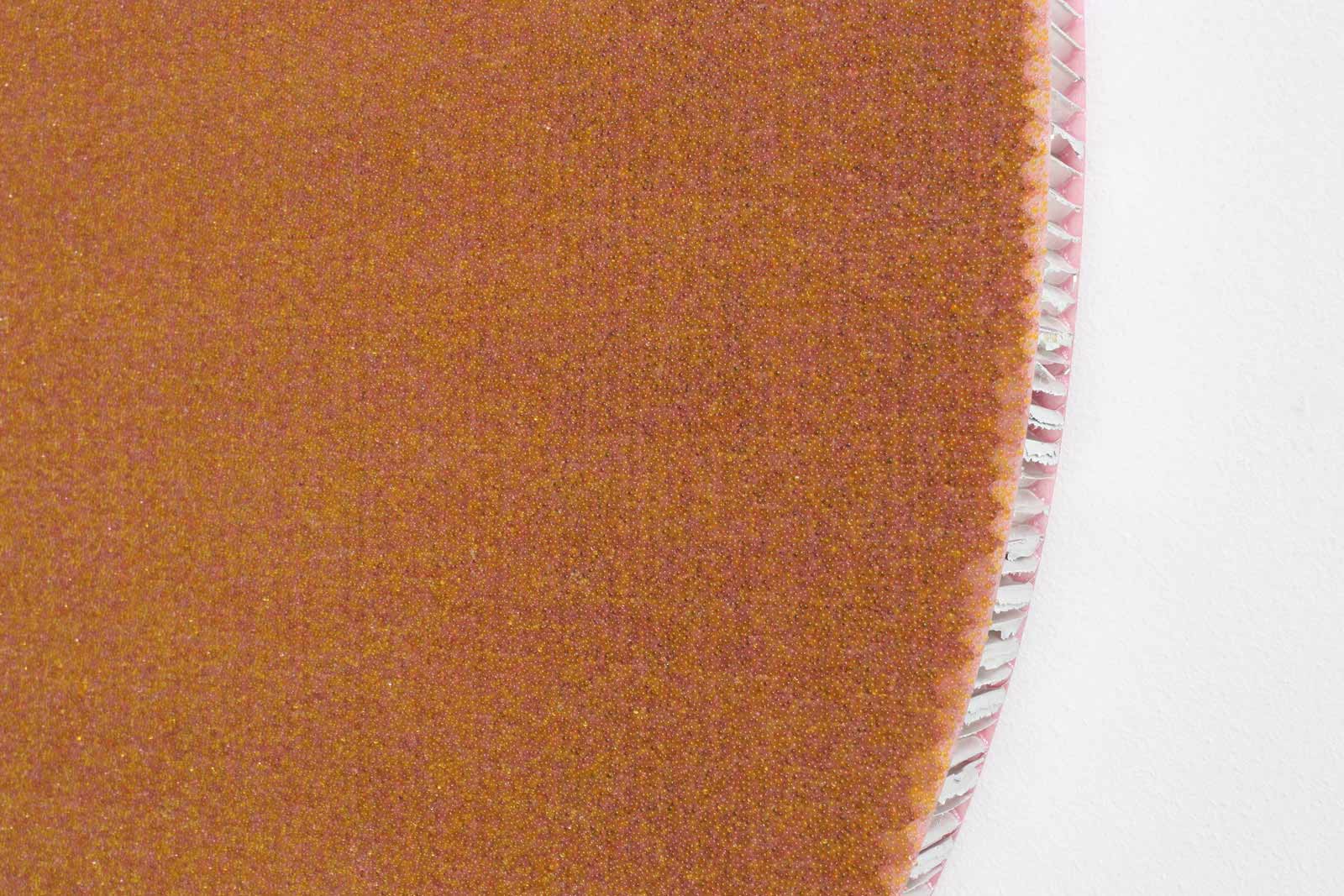

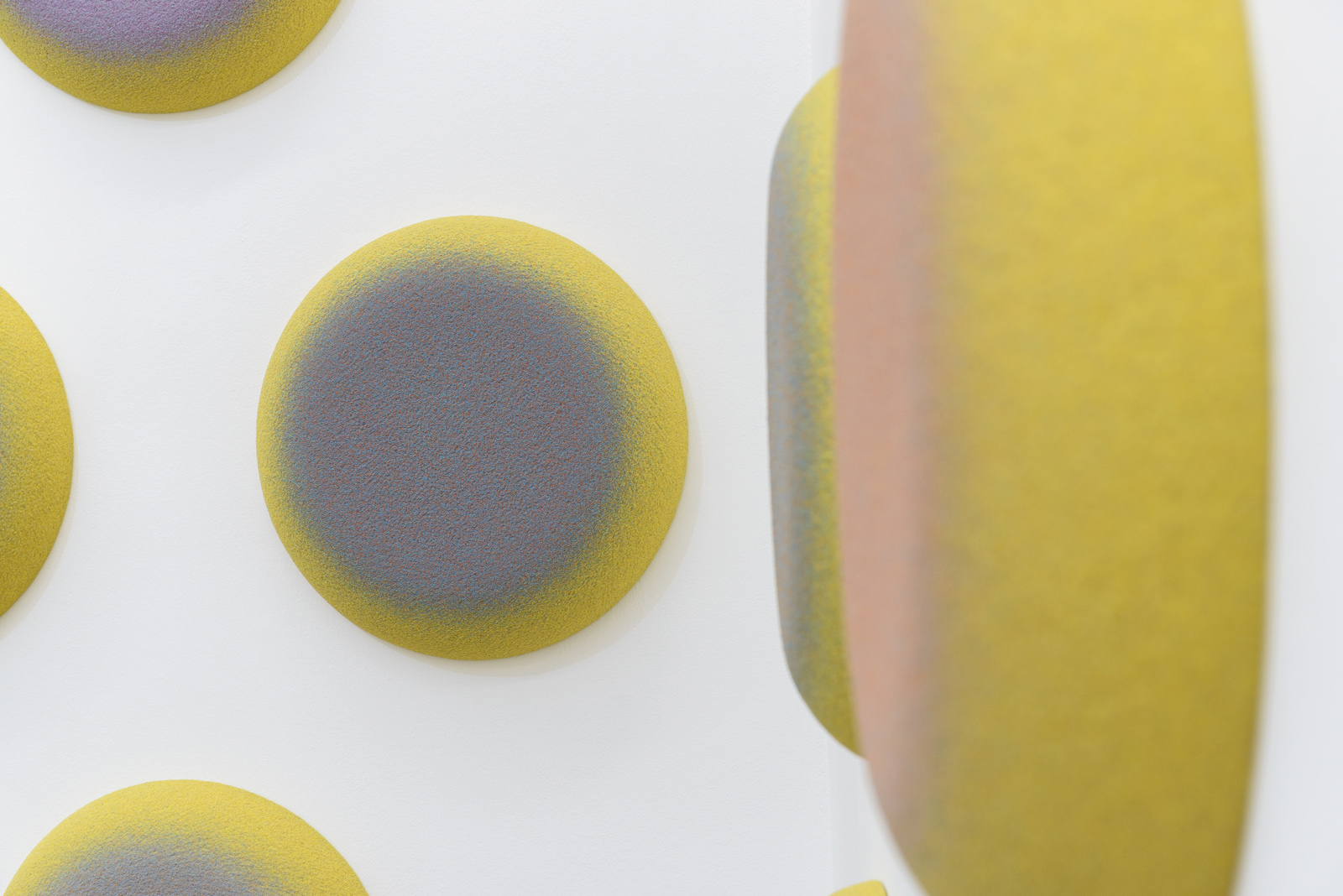

Composite material, quartz, marble.

46 times Ø 71 x 13,5 cm / Ø 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Cheval Blanc Randheli, Maldives.

And we might look at the efflorescence of these spots from a new angle, that of the hypnotic hold (the term hypnotism was invented in around 1850 by

James Braid, based on the technique of staring at a luminous point). By staring at one of these spots, with greater attentiveness, by staring at it with the set

idea of precisely not leaving the vibratory field of this shimmering punctuation, the viewer very quickly feels a soothing sensation, a curious state of

suspension between distraction and absorption. Extracting oneself, meaning abstracting oneself to better experience the sensation of being in the

world. This, as we know, is the challenge of the current revival of hypnosis, a "gentle hypnosis" being no longer perceived as an endeavour of suggestion

and subordination (the myth of the hypnotist manipulating his subjects like mere robots) but rather as an increased vigilance which, to borrow the words

of François Roustang, "allows us access to the power of configuring the world, and existing in a state of dependence on things". In this light, the

fascinating arrangement of Couronne / Crown gives away to an authentic organizing power of the human being in the face of his environment. This is also its fullness, its "lesson of something poetic". Quotation by art historian Pascal Rousseau.

Vincent Beaurin's oeuvre is a sensitive and perceptible exploration of forms and their incorporation in space, "landscape-forms" in which he sets to work on their subtle variations of colours, surfaces and materials with all the precision of an engraver. Each one of his propositions is like "giving formal notice" to forms. What does this mean? It means that the artist questions the appropriateness of the forms he produces by sizing up their boundaries, their limits, and their inflection points: gauging how far it is possible to go to relieve the form of any superficial encumbering clutter while at the same time optimizing its presence in the place it occupies. Producing not objects but places for the gaze to inhabit; conceiving form not as one more form (an artefact) but as a sign in place (a punctuation mark). Through this poetics which involves limits and atmospheric hues, this oeuvre stands apart from the modernist legacy of early abstraction, while linking up with a longer-term history which, from Goethe to Kandinsky, has witnessed the assertion of a way of thinking about form in the process of revealing itself, a "morphology". For the forms Vincent Beaurin summons are above all places in which the visible gestates, places where a presence manifests itself which is the sign of a fullness in the offing.

The Organic Life of Forms and Colours

"The eye sees no form. Light, dark and colour together constitute what, for the organ, distinguishes one object from another, and the parts of the object from each other. In this way, with these three elements, we build the visible world."

Goethe, Introduction to Theory of Colours, 1810.

Everything starts first of all from an experiment involving the links between form, colour and environment. For Cheval Blanc Randheli, an outstanding site in the Maldives, whose more or less unrivalled landscape is a dream décor, Vincent Beaurin has decided to consolidate the punctuation effect (a sign in place) with the work titled Couronne (Crown). This work is made up of 46 units, circular and convex in format, and with the same diameter, covered with a grainy layer of coloured marble and quartz sand, which the artist calls "spots", probably to emphasize the effect of luminous attraction. This tondo-like typology has been an identifiable factor in his praxis since 2010. The 46 spots are distributed in each one of the 46 villas on the site. At once identifiable by their format and unique in their shades of colour, a colour-chart springs to mind (in the manner of the plates of Michel-Eugène Chevreul, workshop foreman at the Manufacture des Gobelins, and a great practitioner of the "simultaneous contrast of colours"), though the variation here does not tally with any declension of the colour spectrum of light, but rather with pure individualized interplays of optical vibrations. Certain tones take precedence, often pastels, and yet endowed with a powerful vibratory capacity. For it is the vibration which here acts as a federating element. Each spot makes it possible to have access to the fullness of the whole.

How does the artist proceed in order to obtain this vibrating effect?

Vincent Beaurin lays claim to and assumes a manual and individualized production of forms, including the most repetitive and even meditative of functions, at a moment when the workshop or studio has often been replaced by the design department. With the studio or workshop (terms shared by the vocabulary of the artist, the artisan and the manufacturer), it is indeed the reconciliation between design and production which is asserted in an extremely cognitive approach to the execution of a work. This is a mastery, or expertise, which Vincent Beaurin acquired at the Ecole Boulle during his years of apprenticeship in the trade of gold- and silver-smithery, when he became closely acquainted with the immediate experience of matter, when shaping a piece of metal called for an intuitive understanding which can only be learnt in the precise repetition of the gesture.

The importance and care which he lends to the making of his sculpture-objects is part and parcel of a mental conditioning. Here we can recognize not only the memory of a philosophical approach to work as an emancipation of the mind (in the manner of someone like Joseph Proud'hon), but also the deliberate choice of a foothold for art praxis in the body/mind relation. The vigilant path of making is at once tension and relaxation, concentration and distraction: a slow appropriation of form. The form of the spots is thus obtained by means of a gradual honing of the block, like direct carving in sculpture, which brooks no mistake, or pentimento. The precision of this carving is the condition which obtains the optimal volume sought. Because how far can you go in reducing volume, without this being done at the expense of the assertion of its physical presence?

The most instructive analogy is that of "swollen skin", a form on which erosion reaches the uttermost point of doing away with it. In the measured swelling of this convex volume, which may call to mind an accidental billowing of the plane, the artist tries to reconstruct a contact surface between what is recognizable and what is no longer recognizable: being at once present, while disappearing as an object, simultaneously defined and elusive. Otherwise put, Vincent Beaurin seeks to produce the fleeting moment when forms are relieved of the identification of an ordinary object, yet without losing the sense of the reality of things. Looking at a figurative landscape picture, the viewer may experience a certain frustration fuelled by the feeling of always remaining behind the window. Looking at an abstract picture, he or she may experiment with the intoxicating sensation of being literally plunged into the landscape, but without any real landmark, and a little lost. For Vincent Beaurin it was thus important to work out an in-between form making it possible to get beyond the window pane (and descend into the landscape), while still keeping one's bearings (and a sufficient distance): "abstracting oneself" from everything while "being in the sensation". As we shall duly see, this is an intermediate state peculiar to hypnosis.

But what kind of presence is involved? We might talk in terms of a primordial or quintessential form, whose unstable outlines are formed and unformed in the passage of colour. This is where the second spot production phase comes in: the coloration of the surface. Once Vincent Beaurin has "made" his form, he covers it with industrially dyed quartz and marble sand with powerful vibratory emanations. To do this, using a previously defined measure, he mixes an amount sufficient to cover the entire spot. After glueing the piece with epoxy resin, he sprinkles the surface with sand. This sprinkling acts as a revelation, in the photochemical sense of the term (in photographic workshops one talks about the silver development of a "rising image", with the somewhat pleasurable sense of an image's magic). The artist repeats this operation a second time after a few hours, the time necessary for the polymerization and drying of the first layer (the second layer making it possible to saturate the sand surface). The number of industrial dyes for the sand is limited, so the artist refines his chromatic variations by formulating his colours himself, with an optical mixture. In so doing, he draws inspiration from the optical laws developed in chromatological manuals, and in particular Goethe's Theory of Colours (1810), and it is to Goethe, prior to Chevreul, that we owe the principle of "simultaneous contrast".

Based on experiments carried out on comparisons of different swatches of colours, Goethe showed the extent to which our vision of colours is altogether relative and fluctuating. Grasping colours now stems from a "subjective" geography of the retina. To this end, Goethe established the famous distinction between chemical, physical and physiological colours. It is this last category that interests Vincent Beaurin. For Goethe, a physiological colour was a colour that is re-composed in the retinal machinery. A green (chemically produced on paper) can be enhanced in terms of luminosity when (in space and time) it is placed close to a red, its complementary hue. Etc. The juxtaposition of the colours with each other introduces a permanent change of shades and intensities. But more than the mere vacillation of colours, it is the way in which the form itself depends, for Goethe, on this luminous shiver. In this way, Goethe carefully reconstructed the physical and temporal development of vision by starting out from the way the eye itself works, with a three-phase function: firstly, a value contrast, then the gradual formation of the colour making a path for itself in the friction between light and dark, and lastly, the appearance of the form. Here he saw the actual origin of the painting project: "In this way, with these three elements, do we edify for ourselves the visible world, and by the same token make painting possible, which is capable of producing on the canvas a visible world that is much more perfect than the real world". With Goethe, painting becomes a matter of contrasts (values/colours), an ever-renewed conflict on the verge of possible overspills, where the eye is permanently looking for a possible symbiosis with the world's luminous activity.

Not regarding colour as a mechanical division of light, an abstract dispersal based on the physical principle of the prism, but rather understanding the phenomenon of colour as a flow, and, just like Goethe did, considering that "light is not visible as light, but only if it appears as an image form" (1). It is this energetic dimension of vision that Vincent Beaurin introduces in the spherical shape of his spots. It calls to mind the extremely Goethean analogy between eye and sun, the ancient idea (we find it as far back as Plato) of an organic identity somewhere between light source and light receptacle: "One then identifies with colour. Eye and mind are in unison with it" (Goethe). With his spots, Vincent Beaurin re-enacts that apprenticeship of the visible, where the experience of vision is based on the recognition of a quintessential image which talks about life itself in the vibration of the light it diffuses. It is here that a thoroughly romantic conception of representation is re-developed, defended by Goethe with regard to artists of the day (Turner was an assiduous reader of his Theory of Colours, which was very rapidly available in an English version), where the eye/sun merger becomes the preamble for a cosmic (and analogical) vision of the activity of the World, divided between the process of engendering colours and the reflection of visible forms whose reflection is just a ceaseless variation of them.

This cosmic sensation is not insignificant in the paradisiac setting of the Chevel Blanc Randheli archipelago. The prospect of the setting sun reflected on the sea is one of the hotel's highlights. Literally located on the seashore, with that sensation of a horizon stretching as far as the eye can see, the villa can simultaneously act as a meditation room and a camera obscura, in an endless mise en abyme-like duplication of perception which plays on the gap between observed reality and inner hallucination. The spot installed above the bath may at once incarnate the reverse image of the sun (the optical principle of the camera obscura) while at the same time giving rise to what Goethe poetically called a luminous or light image (Lichtbild). For these spots subject their grainy coloured surface to the physiological plane of the eye which, in observing the fluctuation of colours and shadows, releases an intuitive sense of the gestation of seeing. The plane of the visible which it is part of, in this immersive and rather contemplative experience, is associated less with an external reality (a landscape, seen through a window giving onto the world) than with a more hallucinatory reality, in complete organic cahoots with the retina which lets us see it. Abandoning a mechanical perceptive system of the coloured surface (which has greatly nurtured the modernist tradition of the monochrome ever since Rodchenko's constructivist proposition and the outlook involving an end of painting, an end that has been forever being postponed) and preferring to it a dynamic vision, included in the time-frame of a revelation that is being forever re-introduced.

This approach, extending to the technical use of a grain of dyed sand which "pixellizes" the coloured vibration, calls to mind one or two precedents which opened the way to the beginnings of abstraction. One thinks in particular of the whole chromo-luminist vein of the early abstract canvases, from Frantisek Kupka to Robert Delaunay, from the Futurist painters (Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini) to the German Expressionists (Franz Marc, August Macke), not forgetting the American Synchronists (Morgan Russell, Stanton MacDonald Wright). Most took up the post-Impressionist legacy (use of the divided touch, the question of the optical mixture of colours, summed up by Signac in 1899 in D'Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionisme). What still remained, with Monet and Signac, where observation of an outside landscape was concerned, was suddenly transferred to that subjective geography of the retina. For it is the body which, in a novel way, becomes the source of a chromatic phenomenon released by the "world of objects" what Jonathan Crary describes as "abstract optical experience", "a vision which does not represent objects situated outside and which does not refer to them either" (2). With, at the heart of this autonomous vision of the subject, the principle of retinal persistence and the so-called "consecutive" or "remanent" image.

Analysis of the colour form that lingers in the retina after being exposed to light or a colour ("successive contrast") takes up a not inconsiderable chunk of the chapter which Goethe devotes to "physiological" colours in his Theory of Colours. But it is to the Czech Purkinje, author of a book titled Contribution to the Knowledge of Vision in its Subjective Aspects (1819) that we are indebted, backed up by drawings, for a more methodical classification of the different types of "consecutive" images (3). Not content with inventorying these different classes of images (stroboscopic effects, physical pressure, galvanic stimulation, distortions, forms of bedazzlement, etc.), he associated them with research into retinal sensitivity which made it possible to draw up nothing less than a "topography" of zones producing coloured images (4). The optical order of the prism may make way for the very Goethean contrast between "hot" and "cold" colours; some colours "move forward" while others "move backward", and their combinations and juxtapositions form something alternating, somewhere between expansion and contraction, where light struggles with shade in a permanent systole which the painter is fond of comparing to the heart beat. Jan Purkinye had already had recourse to this organic metaphor by using in his rotating disks the chronophotographic sequence of a heart beat, whose pace he recreated. What was involved, each and every time, was showing the degree to which the eye is caught by the contagious rhythm of the beat.

But in this use of yellow and its status as a "colour of light" which it acquires in the ensemble titled Couronne, there is also an older reminder of the gilding of frames, the golden skies of icons, and certain backgrounds in works of Cimabue and Fra Angelico. Because Vincent Beaurin likes to regard the history of painting as a large universal encyclopaedia of colour. Prior to physiologists - and their breakdown of the retinal mechanism - it was painters who managed to combine that subtle art of the sharpness of colours with a sense of fullness. And in this respect Goethe was a model, at once painter, watercolorist, and physicist. An art of mixture, experimenting with the culture of pigments. So why, in his spots, does Vincent Beaurin make use of this coloured sand rather than more traditional pictorial pigments? Because of its granulometry or grain measurement. Because this sand heightens the effect of asperity (roughness and shimmering) of the surface and increases the pace of contrasts (simultaneous/successive). As the artist reminds us, the grain size of sand makes it possible to "conjugate several types of contrasts in a mixture." Because, according to the logic developed by Goethe versus Newton, colour is not the result of a breakdown of white light, but rather the outcome of a composition somewhere between light and halflight. For Goethe - and this is a point much used by Vincent Beaurin - colour is, in the first instance, a darkening of light (to this end, Goethe borrowed a terminology from the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher, for whom light was a "lumen opacatum", or "darkened light".) All vision is thus based on the productivity (at once positive and negative) of contrast, margin and boundary. Because of the grain size of sand, these mixtures have more to do with combination than mixture, strictly speaking. Needless to say, other contrasts are present and at work in this type of combination, but, in the spots, the qualities of the exchanges between colours and values also govern the development of the combination of the two main colours: the one that covers that central flat part, and the one that covers the curved peripheral part, as well as the tension produced by this combination (illuminated colour/shaded colour).

Here we gain a better understanding of the artist's choice of this hemispherical hybrid format, because it tends to intensify the optical properties of the edges, which is to say of the outline. Between periphery (curve) and centre (flatness), Vincent Beaurin installs a porous edge which heightens the dynamic value of the surface (image)/depth (background) duel. Vincent Beaurin's spots play a great deal on the principles of refraction, radiation and remanence. The appearance of this coloured plane is the outcome of two simultaneous opposites: one which contrasts the surface with the background, and one which contrasts the light with the dark (shade), with fluctuations in the edges of the colorations which are the actual interplay of the eye's activity. The effect obtained may increase and decrease depending on many parameters (distance from the object, ambient luminosity, etc...); it is never clearly stabilized, the better to remind us that the life of colour is life, period. For this "intensification" of colour clearly points to a form in the making which is not purely quantitative (a measurable degree of luminosity) but qualitative, opening the way to the muddled sense of an evolution (a metamorphosis) which is not only physiological and material, but spiritual, too.

Vincent Beaurin is fond of comparing this effect with that of "the tongue placed on the two plates of an electrical battery". This electrical metaphor is not haphazard. It confirms the magnetic paradigm of a vision based on polarity. Kupka anticipated as much in his famous treatise on La Création dans les Arts Plastiques (1910-1913). In that work he earmarked a great deal of analysis for the eye's physiological functioning, dissecting the eyeball, drawing cross-sections seen from the side and seen head on, and the inner layers of the retina, as if it were important that he enter into the mystery of the chemical transformation from impression (light) to sensation (energy). Supported by many contemporary books on ophthalmology and anatomy, he likened the retina to a sensitive surface made up of cells which transform the impulse of light into an electrical discharge which informs the brain. The eye is literally put in a state of tension, supported by the magnetic power of a series of polarities from which emerges the identity of form and motion (light/dark, hot/cold, eccentric/concentric...).

What, then, might this magnetic conception of vision reveal to us - It incorporates the eye - the way we look at things? (but painting too) in a logic of attraction. By summoning an eye which, seeing such and such a colour, is stimulated to find its complementary hue (its opposite in the chromatic circle), we witness an interplay of reciprocal questioning of colours between them, which tallies with an authentic physics of magnetization. The eye sees orange, and it is already keen to see its complementary hue, blue, in an ongoing quest for the opposite, which kindles the mobility of the retina and reproduces in the onlooker's body the vibratory impulse of the light waves of the outside world. Vibration is thus the outcome of this retinal tropism between the different colours of the prism, finding its peak in the "contrast of luminosity" described by Chevreul, at the risk of overlooking the optical gap between mixture of lights and mixture of matters. Goethe's thinking headed very quickly in this direction, for example in a discussion he had with the poet Schiller, in November 1798, of which, today, we still have the remains of two handwritten diagrams (one defining "the harmony of colours" between them, the other establishing a "symbolic comparison with the magnet"). On the heels of this, Goethe put forward the idea of a "rose of temperaments", by associating the range of colours with a range of emotions (this also marked the beginnings of the vogue for "animal magnetism", with Mesmer). As we can see, he idea of a polarity of colours involves a balance of moods (humours), a clinic of well-being (individual and collective). Many a treatise on colours would advocate such and such a colour for repose, another for activity, and so on... such as we find today in New Age chromotherapy handbooks. This is another possible angle from which to read the spots of Couronne, made for Cheval Blanc Randheli. Without the artist having had to condition the choice of his colours based on a hypothetical taxonomy of care, the vibratory emanations of the spots and the intentional interplay of tension between shade and light can produce in the visitor an effect of relaxation and invigorating exhilaration favourable to the re-creation of a state of physical and mental balance.

This therapeutic dimension of chromaticism is not foreign to a whole "anthroposophical" reading of the vision of colours. One of the great divulgers of Goethe's Theory of Colours in the 20th century was none other than Rudolf Steiner. This was anything but a coincidence. Vincent Beaurin is well aware of this connection, because, in his formative years, he belonged to the theosophical movement - a syncretic line of thinking, created in the late 19th century by Helena Blavatsky, based on the idea of establishing a synthesis between evolutionism, Judaeo-Christian tradition, and eastern philosophy. It was in those esoteric circles, which were deeply attached to making distinctions between different "planes of reality", that many pioneers of abstraction (Kandinsky, Kupka, Mondrian, and the like...) derived certain conceptual motivations favouring a non-figurative manner of representation. We know, in particular, that those painters were directly influenced by the theosophical treatises of Charles Leadbeater and Annie Besant, dealing with auras and the direct vision of thought: or how coloured emanations become the immediate and non-verbal language of moods, visible to the informed eye of certain initiates, prepared by techniques of mental concentration hailing from schools of eastern philosophy (yoga, meditation techniques). This physical influence of colour which Goethe had ushered in with his "rose of temperaments" is present in the effects of auras produced on the surface of the spots. This optical impulse has something to do with the quest for a spiritual animation of matter (aura/anima). We might talk in terms of an animism of paint underpinned by coloured vibration.

The aura effect also refers to what Walter Benjamin meant by this term in his book The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. By aura, as we know, Benjamin understood "the here and now of the work, the uniqueness of its presence in the place where it is found". The aura of the work is what withstands its loss of reality (in the mechanical reproduction of the original, the copy acquires an autonomy which threatens the authority of the initial object) but also its lack of authenticity (the reproducible copy degrades the presence as "actuality", erases all sensation of distance in the easy appropriation of the image, and thereby destroys all feeling of uniqueness and sacredness). So the aura is a matter of presence and distance, of presence maintained in the right distance from the object. This, in particular, is indeed an effect that is used in the spots. Their very tactile and vibratory surface (the grain of quartz or marble sand) lends the objects a powerful presence which radiates all around them, and keeps a distance. Haptic gaze and presence in the place go hand in hand; they are a matter of (con)tact.

Because, with his spots, Vincent Beaurin finds a chance to reconcile the modernist contrast between abstraction and figuration, by means of a form which the history of abstraction had already ushered in (the round tondo-like form was adopted in 1913 by Robert Delaunay in the Premier Disque; as far as the convex curve of the surface is concerned, it was made widespread use of in Californian abstraction in the 1960s). Because what is involved for him, in a more general way, is thinking of abstraction as a perceptible way of finding one's place in the world, in the face of objects, in the face of others, and in the face of oneself, too. And we can thus look at the special configuration of these spots from the viewpoint of the hypnotic hold (the term "hypnotism" was coined in about 1950 by James Braid, based on the technique of staring at a point of light). By staring at one of these spots, with keener attentiveness, by staring at it with the precise idea of not leaving the vibratory field of this shimmering punctuation, the onlooker very quickly realizes that he is enjoying a soothing sensation of relaxation, a curious suspended state somewhere between distraction and absorption. Extricating oneself, which is to say abstracting oneself from the world, in the relief of a possible exit.

As we know, this is the challenge facing the present-day revival of hypnosis, a "soft hypnosis" no longer perceived as an exercise in suggestion and subjection (the myth of the hypnotist manipulating his subjects like mere robots) but rather as a state of heightened alertness which, to use the words of François Roustang, "offers us access to a capacity to configure the world" (5). This kind of hypnosis, which is looking not so much for a malleable person as for a free and open situation, no longer appears today like a sleeping consciousness but, quite to the contrary, as a state of "paradoxical wakefulness", a heightened alertness. Under hypnosis, the subject can rediscover the feeling of "existing in a state of dependence on things", plunged into a force field which is no longer attached by the umbilical bond to a guardian-like or tutelary authority, but underpinned by a relation to the world experienced as a form of self-invention. As seems to be confirmed by current research into neuro-imagery, the consciousness of the subject in a state of light hypnotic induction is no longer that of a self perceiving objects and situations, but rather of an authority previous to the position of the subject facing the outside world. In this sense, hypnosis is less a psychology of altered states of consciousness than a physics of the body, when it is no longer the imagination which gives rise to a state of fascination, but rather the "paradoxical wakefulness which permits the imagination to develop and transform our relations with beings and things." (6). Seen from this angle, the power of attraction and fascination of Vincent Beaurin's spots (we should note, in passing, that sand is an absorbent material, something which, metaphorically speaking, has something to do with hypnosis) makes way for an authentic organizational power on the part of the individual in the face of his/her environment. For the simple fact of staring absentmindedly at the spot, as soon as you enter the villa, may arouse this vague sense of "anticipation" favourable to introspective daydreaming (very akin, incidentally, to the sensation of freedom inspired by travelling and exotic places). What is involved is making the visitor's own freedom tangible, a plasticity in action not aimed at any act in particular, but carried out through resonance, invariably in relation with the surroundings.

An "out-of-this-world" sublimeness

"Some places which we always see as isolated seem to us to have no common measure with the rest, almost out of this world" (7).

For here the notion of surroundings and environment is not neutral. The Randheli site, one islet among a thousand and one others which make up the archipelago of the Maldives, is part of an outstanding geographical setting. A "post card landscape", slapbang in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Far from trying to compete with this panoramic viewpoint which is per se intriguing, Vincent Beaurin's spots play on a subtle art of counterpoint. To do so, it is first important to establish thresholds, territorial delimitations. This is just what the artist does by setting up, at the entrance to the small island, a large arch of welcome. Before setting foot on the island, visitors arriving at the site by seaplane are greeted on the pontoon which then takes them ashore to the island. As a sign of greeting and welcome, they pass by a monumental sculpture installed in the middle of the ocean. The pedestal, set on piles, rises above the level of the water; it is the base for a gate with a highly stylized shape. This arch is at once a sign, identifying the territory, but also the place's symbolic threshold. It is set on an east-west axis, 500 feet from the shore. From a distance, you glimpse a very graphic arabesque which surfs on the beach, like a wave. You can also make out the spare, refined shape of a double equine silhouette (an almost subliminal image of the "Cheval Blanc", or White Horse), which gradually turns into a gate of greeting and reception, a threshold which fully signifies a passage towards another world. There come to mind certain coded forms of mosque architecture, in particular the mihrab (which means "sanctuary" in Arabic), the niche indicating the direction of Mecca, decorated with two columns supporting an arch. Some forms of mihrab (the one in Qom especially) are known as "gates of Paradise". Pursuing the westward direction, the Torii also comes to mind, in particular the one in the sanctuary of Itsukushima, in Miyajima, in the once ravaged province of Hiroshima in Japan. There is nothing religious about the Randheli gate of greeting; it is the signal that you are entering a thoroughly earthbound paradise, it is intended to protect the place of welcome, like somewhere holy or sanctuary-like: we are entering another place, a place that is not only "exceptional" and "extraordinary", but also "out of this world".

Vincent Beaurin makes no bones about playing with this symbolic displacement of forms (effigy/sign/signal). This gate is, for all practical purposes, a statue (an object placed on a stand), a camouflaged equestrian statue. The effigy set on the stand has been refined to such a degree that it loses in identification what it gains in monumentality. But what is involved here is not a lightening of the sign: the adjusted form rightly keeps a measure of complexity in its reduced state. This, incidentally, is what one senses in a definition of volume which has more to do with an extreme tension of form than with its erosion (becoming extricated from the image): tending towards a quintessential form of the living which has shed those attributes which are too anthropomorphic. Furthermore, the upper line of this gate, its archway, calls to mind a drawn bow. From arch to bow, and vice versa, the better to signify this effect of extreme tension. In this context, to draw out the metaphor of aerodynamic streamlining, we might talk of a furtive, stealthy object, the way we now talk of stealth aircraft (at once monumental and invisible). Seen sideways on, the statue becomes a simple vanishing line. Seen head on, it becomes a monument. This gate is just as much a threshold as a passage between visibility and invisibility.

This time around, for technical reasons, the statue has been made not in the artist?s studio but in a shipyard on France's Atlantic coast. The figure weighs 200 kilos (440 lbs.) for a monument measuring more than five metres in width and four in height (16 x 13 feet). The structure is hollow, made using composite materials, glass fabrics, polyurethane foam, and epoxy resin, and covered with an 'antifouling' paint (containing biocides designed to prevent seaweed and living structures becoming attached to the underwater shells), consisting of 99% pure copper powder, and resin. Copper catches light, playing with sumptuous reverberating effects, and glints in the sun, like a large mirror. This copper is meant to oxidize (in this way the statue will record the activity of the water, the ocean, and the sky); the sedimentation of the layers will form a skin which will become veiled over time, coloured with quite a bright Veronese (emerald) green. This is what lends it a pictorial dimension, with this same play on the ambiguities of its differing aspects (rough and soft, absorbent and reflective, luminous and opaque), and this same epidermic character that occurs in the spots, as if it were a matter of reminding us how hard it is to talk about articulation and contrast without bringing in the extremely sensitive difference between rough (hard, tough) and soft (limp, encompassing).

This interplay of difference and alternance (perceptible/abstract) is part of this curious impression of being "almost out of this world", and having "no common measure with the rest". An interplay involving the positioning of forms and signs, with a very keen sense of place and spacing, but also of trajectory, rhythm and pace, and difference, and a fondness for punctuation, where objects are placed like the words of a cryptic sentence, where signs have become the hieroglyphs of something imaginary to be deciphered, which does not connect with anything, if not to something which would always have to do with the physical space of contemplation. First of all, there is the place occupied by the spots in each of the villas. It is not haphazard or insignificant, incorporated as it is, as we have seen, at a distance, in the axis of the entrance gate, like a target. When visitors enter their bedroom, they are riveted to this point which radiates over the whole space, and lends it a chromatic note. The spot does not merge with the room's furnishings; it stands markedly apart, while at the same time producing a sensation of ambience just above the bedroom's large bath. As in Proust's novelistic world, we can talk here of discontinuous spaces, enjoying an extra-territorial privilege. The spots are placed in a state of weightlessness; the arrangement is abstract, producing a curious sensation of discrepancy in relation to reality: art has to create something different.

For far from being frozen, the form of these spots is in fact always moving and shifting. Placed at eye level, in a very aerial situation, the spots take on a star-like look, and their distribution in each of the villas is constellation-like. It is here that they unwittingly introduce an uncertain ratio of scale. Are they large or small? What scale (macro/micro) are we on? Out of scale, "almost out of this world". Here there is both measure and excess, in an "in-between" set which, in its own way, refers to a classical polarity established by Kant between the beautiful and the sublime. For Kant, the beautiful is associated with measure and moderation (the right arrangement of parts), while the sublime stems from excess and immoderation. The former persuades, the latter delights; the one suits, the other disappropriates. With these spots, Vincent Beaurin subtly plays on the difference between these two manners. Through its curved form and its chromatic saturation, the spot produces a sensation involving something wide and yawning, into which the visitor may project himself: a cosmic abyss, calling to mind the visual sensation of Lucio Fontana's Concetto spaziale works, in the intoxicating quest for dizziness, a form of immediate abandonment in the pure sensation of colour. This is its hypnotic aspect. But these spots are also drawn-up geometric forms, with carefully defined outlines. Places where the visible is mastered by the arbitrary nature of geometry. To describe the sense of beauty, the Greeks and the Pythagorean tradition used the words symmetria (measure) for sculpture, and taxis (order) for the visual arts. Here, symmetry is evident in the installation of the spots in the middle of the room, but it is disturbed by a spatial placement which overtly seeks to go beyond the morphological limits of sculpture, to endow it with a more metaphysical aura.

The first effect of confusion is the suspense of the coloured form. This suspense, which Edmund Burke had already identified among the symptoms of the sublime in art (8), manages to be developed in many different ways, the most obvious of which is the way the forms actually take flight. In the fuselage of the form there is something specifically aerodynamic, a "streamlined" effect. But there also comes to mind the idea of a shift of surfaces. The material which Vincent Beaurin uses for his spots, quartz and marble sand, gives a special grain which calls to mind the roughness of a wall rendering. The object stands out from the wall (it makes itself conspicuous) while at the same time merging with its material plane. Here, in a hijacked way, we find the principle dear to the neo-plasticism of Piet Mondrian, that of a possible fusion between the volume and the two-dimensional surface of the plane through a movement of the plane-space. With, as a theoretical corollary, the suspicion of what, in a closed way, might typify the formal bases of each one of the art praxes (painting, sculpture, design, architecture), regardless of the environment in which they are incorporated. The spots are thus experimental models of form, "monuments as abstract forms", as the Polish abstract painter Wladyslaw Strzeminski was fond of putting it, he who was close to the Suprematism of Malevich, for whom painting was bothered by the fatality of illusionism, and architecture by the circumstances of its functionalism, so sculpture became the sole territory of utopian experiments involving forms, the playground of atopia.

But unlike the projects of Strzeminski and Mondrian, the relation with the architectural environment does not have to do with integration. For Vincent Beaurin, what is rather involved is guaranteeing the autonomy of the work, and its singularity, and dealing with its particular time-frame. Each one of his spots plays on a subtle variation of shades and tones, where light and shade orchestrate different scores which are incorporated in time. For, every time, the artist simultaneously emphasizes the singularity of the object and its radiating sphere of influence in the very place where it is put. The sophistication of the matt and radiant surfaces rules out any excessively literal approach to sculpture, and invites viewers to enter into the object's own particular life. This variation on one and the same geometric module echoes the serial practices of those Minimalist artists who made widespread use of the repetition of a simple geometric form. But precisely where modernist tautology won out over the Minimalists, in systems of iterations which systematically brought the phenomenon of equivalence to the fore, Vincent Beaurin tends rather to give precedence to the principle of difference ad minima. And when the Minimalists sought to freeze the time-frame of the work (the present time of observation; the bygone time of production), Vincent Beaurin likes underscoring the ongoing updating of sculpture's internal time: its animation within the rhythmic value of tempo.

It is possible to readily associate this "musicality" with the metric advocated by Plato in Timaeus. In this dialogue, the hold of geometry over representation corresponds to a definition of space (the extensio) that can be reduced to a series of relations. In the matter of this extensio, Martin Heidegger talked about that capacity for construction "of things which set up spaces" (9). Sculpture is not in discussion with space but an "incorporation which gets places to work, and with these latter brings an opening up of lands for possible inhabitation by human beings." (10). Khora, a receptacle of form in Timaeus, and a place of inclusion which goes beyond the boundaries of the perceptible and the intelligible (11), provides a poetic and abstract model for this art of contemplation to which Vincent Beaurin invites us in front of his spots and his arch. He offers us a clue for understanding this art involving a minimal congestion of form in space, a clutter which has the value of a signal. With Couronne and with Arch, Vincent Beaurin tells us the extent to which these forms in suspense are not merely signs awaiting meaning, but also living ideograms which talk to us about life itself in the physiological activity of line and colour. The strategic choices to diminish the figure (but also the production of objects whose sole transmission is precisely that of a reflecting signal which indicates a presence) are so many moments of assertion: removing everything that may create unresolved tensions which alter the effectiveness of the sign. Or how to render a place singular by means of a sign which already points to its force, therefore beyond any conception of space as a limited resource. "Today", the artist tells us, "space is no longer grasped by way of its expanse, but through a certain concentration, the place. When this latter is efficient, we may then talk about presence". Herein lies a thoroughly romantic interpretation of that Baudelairean luxe, calme et volupté - luxury, peace and pleasure.

Notes:

1-. J.W.Goethe, Matériaux pour l'histoire de la théorie des couleurs, trans. Maurice Elie, Toulouse, Presses Universitaires du Mirail, 2003, p. 297.

2-. Jonathan Crary, op. cit., p. 196.

3-Jutta Müller-Tamm, "Die Empirie des Subjektiven bei Jan Evangelista Purkinje. Zum Verhältnis von Sinnesphysiologie und Ästhetik im frühen 19. Jahrhundert", Studien zur Geschichte visuelle Kultur um 1800, Dresden, Verlag der Kunst, 2001, p. 153-164.

4-. Nicholas J. Wade, Josef Brozek, Jiri Hoskovec (ed.), Purkinje's Vision. The Dawning of Neuroscience, London, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2001. I am grateful to Javier Arnaldo for having suggested to me the comparison between Delaunay's Autoportrait and the Purkinje phenomenon.

5- . François Roustang, Qu'est-ce que l'hypnose?, Paris, Les Editions de Minuit, 1994.

6- Ibid., p. 14.

7- Marcel Proust, A la recherche du temps perdu, vol. III, Paris, Gallimard, 1988, p. 393.

8-Edmund Burke, Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), edited by B.Saint Girons, in Recherche philosophique sur l'origine de nos idées du sublime et du beau, Paris, Vrin, 1990.

9-Martin Heidegger, "Bâtir, habiter, penser", Essays and lectures, Paris, Gallimard, 1958, p.189.

10- Martin Heidegger, "L'art et l'espace", Questions IV, Paris, Gallimard, 1976, p. 105.

11- Jacques Derrida, Khôra, Paris, Galilée, 1993.

Pascal Rousseau, born in 1965, is Professor of Contemporary Art History at the Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne. He has curated the exhibitions "Cosa mentale. Imaginaries of Telepathy of the 20th-Century Art" at the Centre Pompidou Metz (2015), "Fabrice Hyber. Pasteur'Spirit" at the Institut Pasteur, Paris (2010), "Sous influence. Résurgences de l'hypnose dans l'art contemporain" at Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne (2006).

Full circle

Pascal Rousseau

2014.

Translation Simon Pleasance.

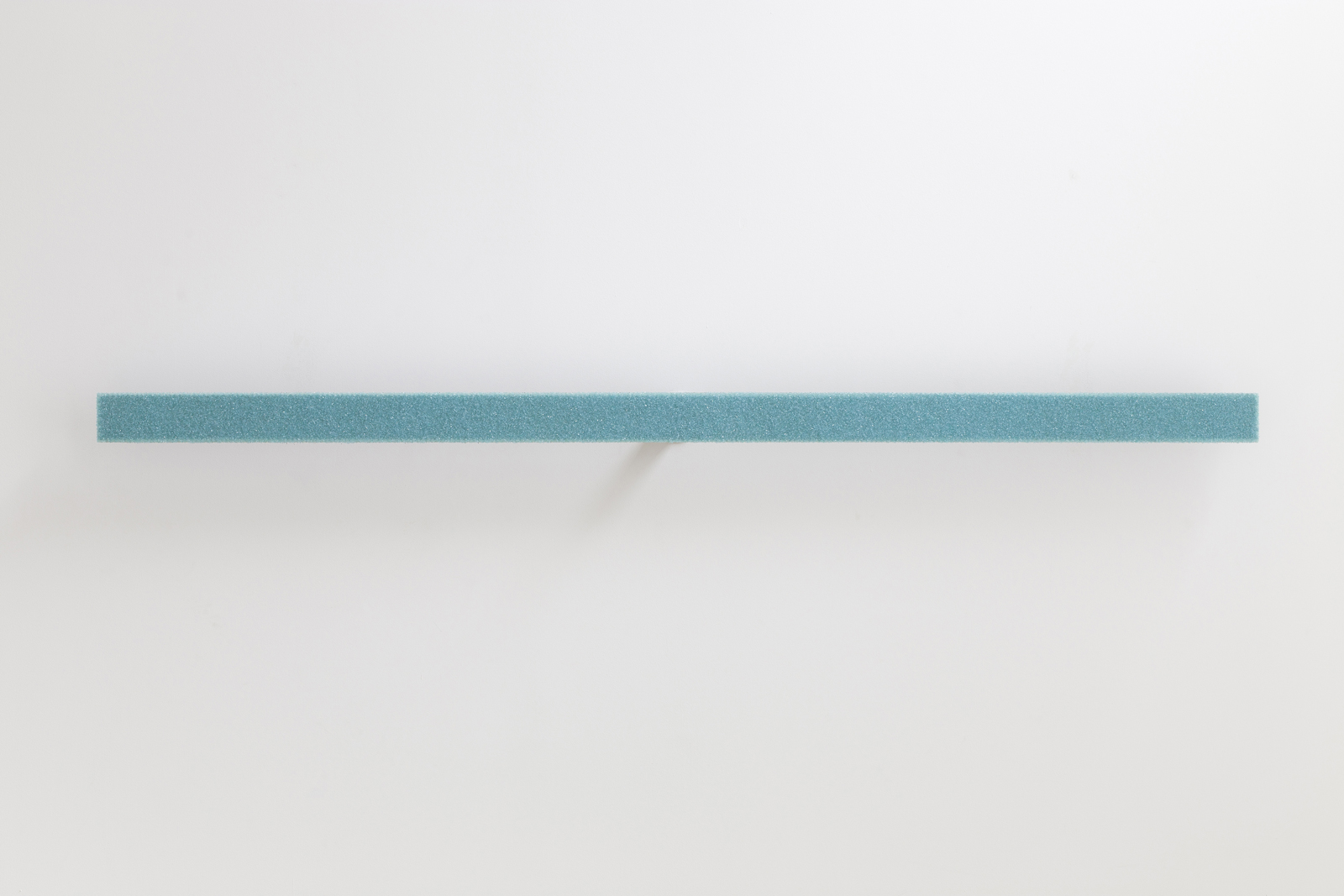

Stainless steel, composite material, glass.

7,5 x 177 x 12 cm / 2 3/4 x 69 1/2 x 4 1/2 in.

VB_2016_08_21

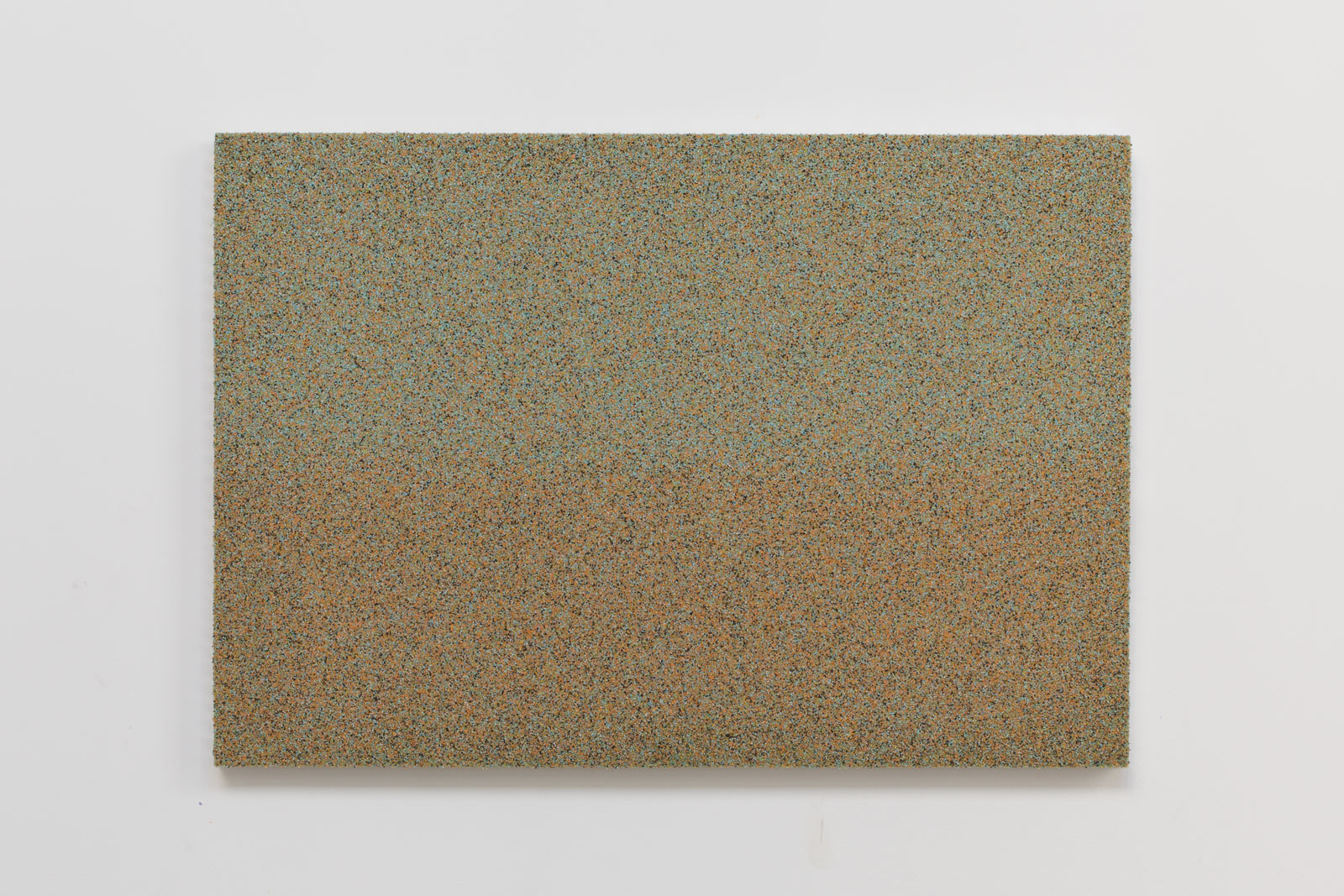

Composite material, quartz, marble.

46 x 65 x 1 cm / 18 1/8 x 25 5/8 x 1 in.

VB_2016_08_12

Composite material, quartz, marble.

15 x 21 5/8 x 1 in.

Unique

Polystyrène, époxy, sable de quartz, sable de marbre.

Unique

Composite material, quartz, marble.

33 x 55 cm / 13 x 21 5/8 x 1 in.

VB_2016_08_10

Polystyrene, epoxy resin, quartz sand.

Ø 71 x 13,5 cm / Ø 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique