Loading...

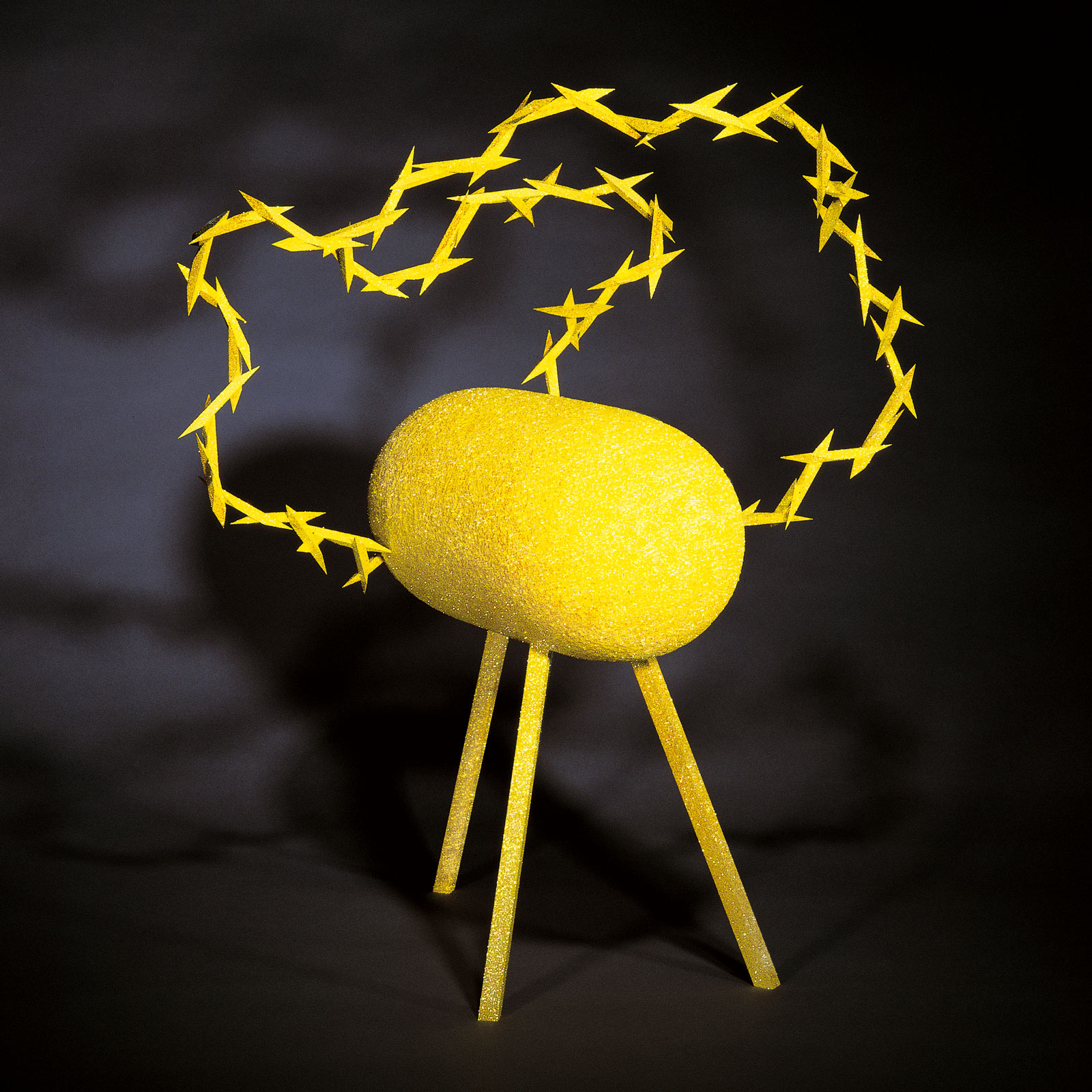

Polystyrene, glitter.

25 x 19 x 15 cm / 9 7/8 x 7 1/2 x 5 7/8 in.

Unique

Polystyrene, epoxy, glitter, sand

Ø 107 x 51 cm

vv

Polystyene, glitter.

13 3/4 x 15 x 3/4 x 4 in.

Unique

Polystyrene, glitter, flint, school benches, sodium lighting.

340 X 1200 X 695 cm / 134 x 472 x 274 in.

Unique

MUDAM collection, Luxembourg.

Polystyrene, glitter, flint, school benches, sodium lighting.

340 X 1200 X 695 cm / 134 x 472 x 274 in.

Unique

MUDAM collection, Luxembourg.

Polystyrene, glitter, flint, school benches, sodium lighting.

340 X 1200 X 695 cm / 134 x 472 x 274 in.

Unique

MUDAM collection, Luxembourg.

Vincent Beaurin is an artist. Since the 1980s, he has been carrying on a strange conversation with objects. How should they be modelled, represented and presented? How can they be made to exist in a way to give them meaning? So that they hold true? So they don't cave in on themselves, in a ridiculous fashion, like a cake that sinks? His answers may be angry, or tender. The objects are sometimes very small. You could hold one in the palm of your hand. On the floor, in a corner of the workshop, there is a strange pile of shards of glass and flint. At first glance, it looks like there has been a recent mishap. But then you see that that is where he has been working, breaking off chippings, like a road labourer. Some objects are gigantic. You have to raise your head to look up at them, and then you'll suddenly see clouds of tiny little hemispheres. Whether large or small, the objects form part of an ensemble. It's all about scale. Of how the Milky Way would appear, or an ancestral animal, a geometric emblem, or a level crossing.

P.C. You are a sculptor, why do you sculpt?

V.B.....

P.C. Not a good start. He is not answering my first question. Let's try the second. What can you say about the material you use, polystyrene?

V.B. Nowadays, many things are very light. A minimum of material can cover a large surface area and fill a considerable volume. Polystyrene is the solid material whose materiality comes the closest to zero. It is as white as the snow in the Ardennes, from where I come, and it sparkles like snowflakes. It is easy to use. I can do everything myself with a minimum of tools. I scratch, I scrape out, I stretch it and it breaks into crumbs, like eczema, skin-deep.

P.C. And your tools?

V.B. When I started at the École Boulle, I had to make my first implement, as it was something you couldn't find in the shops. I was in engraving, the silversmith's trade. I made a fuss so as not to go back to the workshop. I wanted to be doing sculpture. However, I learnt a lot more while engraving. We did everything, from A to Z, except smelting and gilding. Afterwards, for more than fifteen years, I paced all sorts of different factories and workshops, for my research and production. I made things and watched others make things, and with the most sophisticated to the most archaic tools and techniques, in a large variety of materials. Now, I am sculpting polystyrene with a grater that I made myself, from a little board and some nails. I paste with a brush and sprinkle flakes with a sugar shaker. For cutting the flints, it's stone against stone. I depend on nothing and nobody. It is an economy. And it goes so quickly, as an appearance.

P.C. You produce objects in the form of sculptures which look as if they come from another planet. You use the specks. Do you see art as a spectacle?

V.B. When I go to a preview, which is quite rare, sometimes I see the spectacle of art. But no, art is not a spectacle. Art borrows from lots of different fields without being assimilated into them. The specks are like pulverized mirrors, millions of sparkles of colour.

P.C. You have been at the threshold of art and design. You were in the first art-design exhibition at the Emmanuel Perrotin gallery, in 1995. Today, many artists make tentative steps towards design, but then often become discouraged through failure, because they don't understand the problem which needs resolving. They are not really interested in what is at stake, of making a part of the environment. For example, they don't have the right scale or a suitable volume. What do you think of the performance ?art-design??

V.B. Nothing. Twenty years ago, I painted beautiful pictures, but it was only myself they brought joy to. This seemed pointless. So I looked at objects that people use. I said to myself that if I made a chair, other people could at least park their bums on it, there would always be that. That's how I became interested in design. Art, design, architecture, the graphic arts, fashion design. Each of these areas requires specific skills. I am unconvinced that these disciplines can be likened to each other. And it no longer interests me. But on the subject of the correct scale, a flower and a star are different sizes, but they can have the same scale. That is how you can compare the vault of a cave with the vault of heaven, and you can draw the sky. (He rises, takes up a book, and shows me prehistoric paintings in the Chauvet cave.) It's what's known as a decorated cave.

P.C. Ghislain Mollet-Viéville, an art agent, said: ?Design seems to me to have been very creative for a long time and today, it is exhibited legitimately in art venues. I am more attracted by culture than by art with a capital A?. So?

V.B. So? For me, it's the opposite. Culture is associated with group customs, it's gregarious. Art is something else. You could say it's reactive. Perhaps this is what he had grown weary of. Admittedly, you can do a lot of things with creativity, but there is no more legitimacy in design than there are galley convicts in town!

P.C. To be an artist, is also to exchange. What do you exchange with others, where do you cross others, where do others intervene?

V.B. My work is made up of creating a device which excites the visual acuity of the person looking at it. Representation limits you to seeing only one point of view. To step outside of yourself, to go further than your own boundaries, is also to accept that this can stay mysterious and strange. Not all experiences are communicable. Intimacy is shown intimately, and not to a group. Exchanges allow you to circulate your work, to pay the rent and to buy a train ticket.

P.C. In your work, on one hand, you have represented animals, landscapes, portraits, a whole neo- figurative world. On the other hand, we find radical geometric shapes like the cone, mooring posts, multitudes of spheres and hemispheres. It's a very conceptual display. And somewhere between the two, we find something Shamanic, the Beuys side to your production, rather mysterious and profound, like the apprenticeship of flint-cutting, an ancestral practice, a basic concern, dating back some hundreds of thousands of years. You find, for example, enigmatic shapes pierced with a hole which is plugged with a glass eye, a glass eye sharpened like a flint. Explain to me how you follow these different paths?

V.B. The role of meaning is to produce order. When things are not under this yoke, they seem to be fragile, like images, with no links and no coherence, no density. That is how I see things and how I move through them. Images that have drifted or are slanted. I see darkness behind them, absence. Art is the place from which we escape order.

P.C. Here in Luxembourg, you have used a large room, a sort of hall or antechamber, between the main foyer and the cloakroom. It's a place where you take off your coat, and get comfortable. On five walls, there are clouds of hemispheres that sparkle like stars. One of them evokes a cave entrance, another, a hill or a dormant volcano, or perhaps a universe which is forming. Three pieces are arranged on the sixth wall. The first is the head of an imaginary animal with an eye of black flint, the second is like a tuft of hair in a firecracker, a meteorite or a mushroom, and finally, the third is more abstract, a cone shape. In the middle of the room, there are two large benches which you found in England. You can sit on them. It's a very rich idea, this moment of transition between outside and inside, in a place where the works of around forty artists are exhibited. And there is a lot of light, a strong light, golden with pink notes. There is a strange and amazing atmosphere, as soon as you walk into the gallery.

V.B. But, there's no question?

P.C. That's true, it's an answer without a question. All right. What criteria do you set yourself for your representations, and for finding new shapes?

V.B. I don't set anything for myself. I am restless. I want to see and do, to see more and make things to be seen. I don't represent. I observe. I search. I return. I set down. I move. I speculate. I feel. I articulate. I note down. I point out. I don't find new shapes. They are already there. All that is needed is already there: the images. Those are of the things which surround us. Those which flash before us. Those which interfere, as if in a dream, or those which I want, of which I am curious and which show themselves to me.

P.C. Can you describe an anecdote from your career.

V.B. Ten years ago, I visited San Marco Convent in Florence, and its Fra Angelico frescoes. They are incredible, Fra Angelico, gentle. Fresh and delicate. One falls in love with the Virgin. It's difficult to put into words. They are intimate, indescribable. (He takes down from the workshop wall a reproduction of a fragment of a painting on wood, an angel in pink, with blue wings. He shows me images in which we see caves and mountains.) The Fra Angelico frescoes are my greatest love. Just to speak of them makes my heart swell.

P.C. And a personal anecdote.

V.B. The death of Jimi Hendrix, when they announced it on the telly. I was eleven or twelve. P.C. What piece do you feel like now?

V.B. The god, Pan. With no arms or asshole (he shows me a model). With a single leg ending with a hoof. His wounds are of flint. He is crying out in pain, with his back arched, and his backside in the air.

P.C. Are you all right?

V.B. I'm very well thank you. In fact, I have never been better.

P.C. What are you looking at, at the moment?

V.B The same thing that I have always been looking at. I am in a cave and I am scrutinizing the rock face. I want to cross to the other side, to jump outside myself. That's why I look at objects which are 20,000 years old. I also look at humans, in the same way that they generally look at other animals. And do you want me to tell you what I see for once?

P.C. Yes.

V.B. Well, I see a herd of beasts in a botanical garden, who have not yet been there for a few hundred thousand years, and yet many of them already claim that this has always been their home, because they had a bad dream or a bad encounter the night before.

P.C. Does the word display mean the same thing, for you, as the word installation?

V.B. No. Because the different elements that make up a display are autonomous, whereas an installation sends them back to their state of alienation.

E N D

THE FUN OF THE PAST?

Interview by Pascaline Cuvelier.

Vincent Beaurin Exhibition 2006, MUDAM.

Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain, Paris.

Polystyrene, wood, glitter, light bulb.

450 x 500 x 750 cm

Private collection

Polystyrene, wood, glitter.

100 x 80 x 60 cm / 39 1/4 x 31 1/4 x 23 1/2 in.

Unique

Various materials

Various dimensions

Various materials

Various dimensions