Notes on NUN

I've often involved at once strange and familiar legendary beings, designed and made to perform, but showing severe afflictions.

These transfixed beings, like recent impacts, gave rise to both sympathy and empathy. People could identify with them.

This time, in front of a field of sparks, and behind the volume which might tally with its imprint, the spectator should be able to perceive his substratum.

For the first time, I am borrowing from the human figure.

Involved are three standing statues of one and the same species, like animals or plants, or stones sharing certain features.

The pedestal which the effigy stands on is to the statue what the stick of wax is to the candle.

Their motionlessness seems definitive. Yet they appear to make the air vibrate.

It is not a question here of an alternative, a back-and-forth between a here and an elsewhere, or between the visible and the invisible, a to-and-fro from life to death or some other life, nor is it even a matter of something different, but rather of an abstraction, a withdrawal, and an opportunity to abstract oneself.

Nor is it a question, either, of transcending anything, not that I oppose transcendence with immanence, and have to take sides with one against the other, but rather that the transcendent proceeds too often by way of a deceptive division of the world, or even of a complete malevolence with regard to creation.

The presence of these statues seems permanent. The transcendent alienates the there to so-called higher and ineffable planes, which are definitely inaccessible. The transcendent has emptied the there of its substance.

The conception of death is associated with the conception of space and time.

The Egyptians seem to have been fascinated by death, but they had a different conception of space and time. I don't know anything about the Egyptians, but this is what I sense and it is possibly what attracts me in the objects they left behind, another conception of space and time, and therefore another conception of death.

Death now seems to me like a limit, or boundary, an end which leads straight to the essential, the foundation, the raw stuff.

Death is a door for the living. I call the living those who, like me, have assimilated a vision and a discontinuous conception of life and death, and who grasp space through depth and time through history, a conception, rather than a vision, which is completely mistaken. Death offers access to the substratum. The living are able to represent the substratum for themselves, by mentally drawing closer to the end of their life. This, anyway, is the impression I have, and what I feel.

In Turin, at the Egyptian museum, on the whole inner surface of the first wooden envelope containing the mummy, painted black on white, I saw the book of the dead. All those little signs are like the slivers of a shattered mirror. I don't know what the dead see, if they even see anything, but this representation is quite close to what I perceive and the way in which I myself have represented it.

When I focus on the end of my life, the way I imagine it above, which I manage to do for a few seconds, which isn't easy because of my culture and my education, it gives me a sensation of fizzing, gentleness and fullness.

When I stand attentive and calm in front of the flat surface of one of my statues covered with a billion tiny splinters of coloured glass like the slivers of a shattered mirror, I feel the same thing. I imagine the substratum.

My work has always given me enough satisfaction and pleasure to carry on with it. Every day it enables me to get away from myself. I've never laid claim to inspiration, nor have I looked at myself in my work, or even less, have I identified with it. Today, though, rather than experimenting with the system or arrangement I am working on, I project myself into it. I get involved in a meeting with myself, in the flaying of my breathing. Like Rembrandt, I make my examination, without falsehood, a real assessment, a panegyric even, of the volume which I clutter, which I fill, without indulgence or artifice. And it is a body that one sees, and recognizes. Whereas, in reality, I don't know how to say it any other way, what is involved is just a cavity, a hollow, a depression. We see everything the wrong way round. We have identified, assimilated the body, bodies of all sizes, of all shapes, to the solid, whereas it is the opposite. It is precisely the opposite. Any object or body, cumbersome and assimilated as such, is like a bubble in water. And it is only in the section of this bubble that we have access to the substratum, nature even more than fullness.

The mummy is not simply the embalmed remains of the deceased, but a witness or magical load around which the successive envelopes of the sarcophagus correspond to the different bodies or states of consciousness of a kind of avatar of the person.

This is where my statues differ from Egyptian sarcophagi, even if they may bring them to mind. They don't contain anything.

Vincent Beaurin, January 2019

Translation Simon Pleasance

Polystyrene, glass, wood

200 x 47,2 x 49 cm

Unique

Polystyrene, glass, wood

200 x 47,2 x 49 cm

Unique

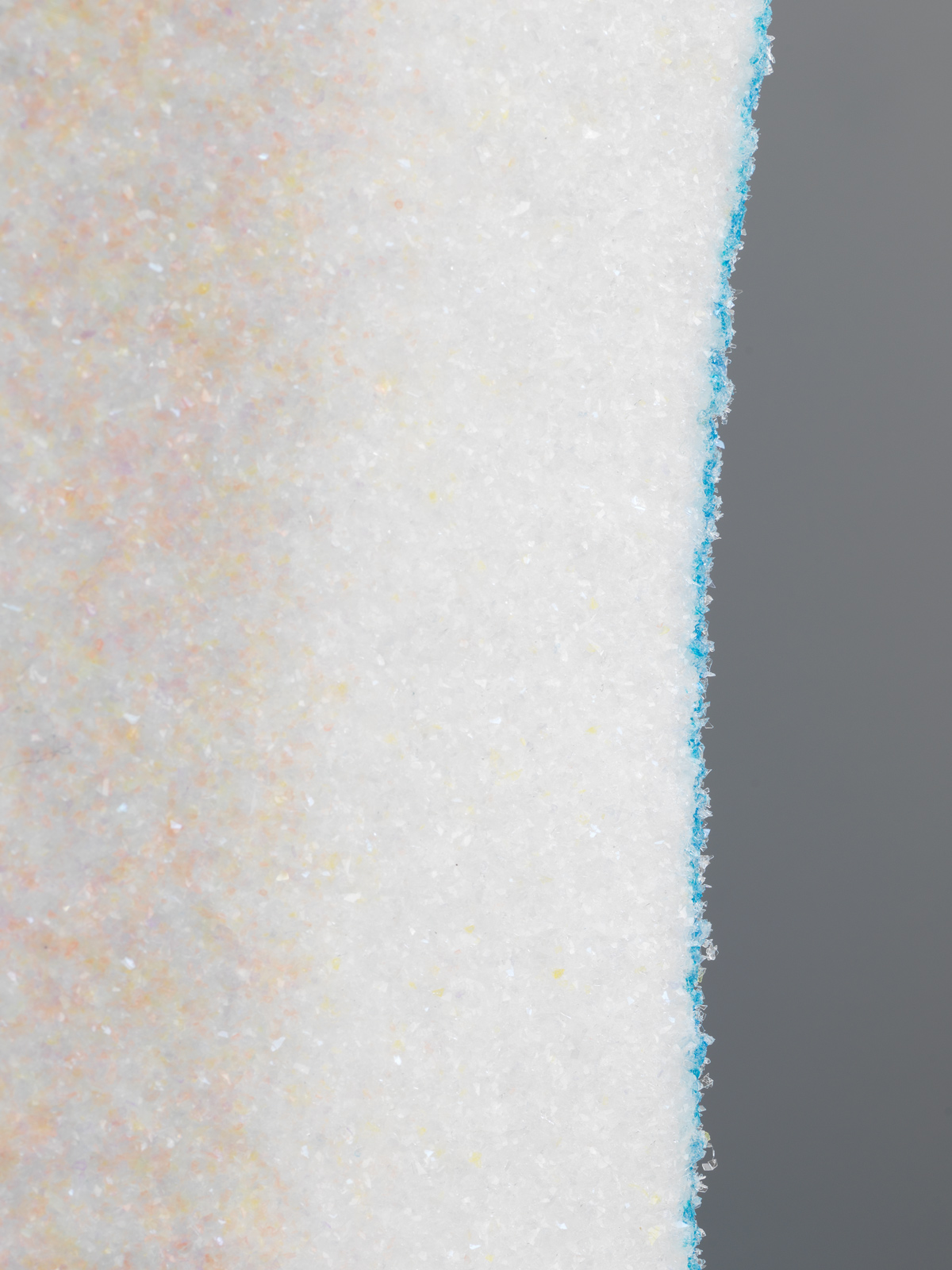

Detail

Polystyrene, glass, wood

200 x 47,2 x 49 cm

Unique

Polystyrene, glass, wood

200 x 47,2 x 49 cm

Unique

Polystyrene, glass, wood

200 x 47,2 x 49 cm

Unique

Detail

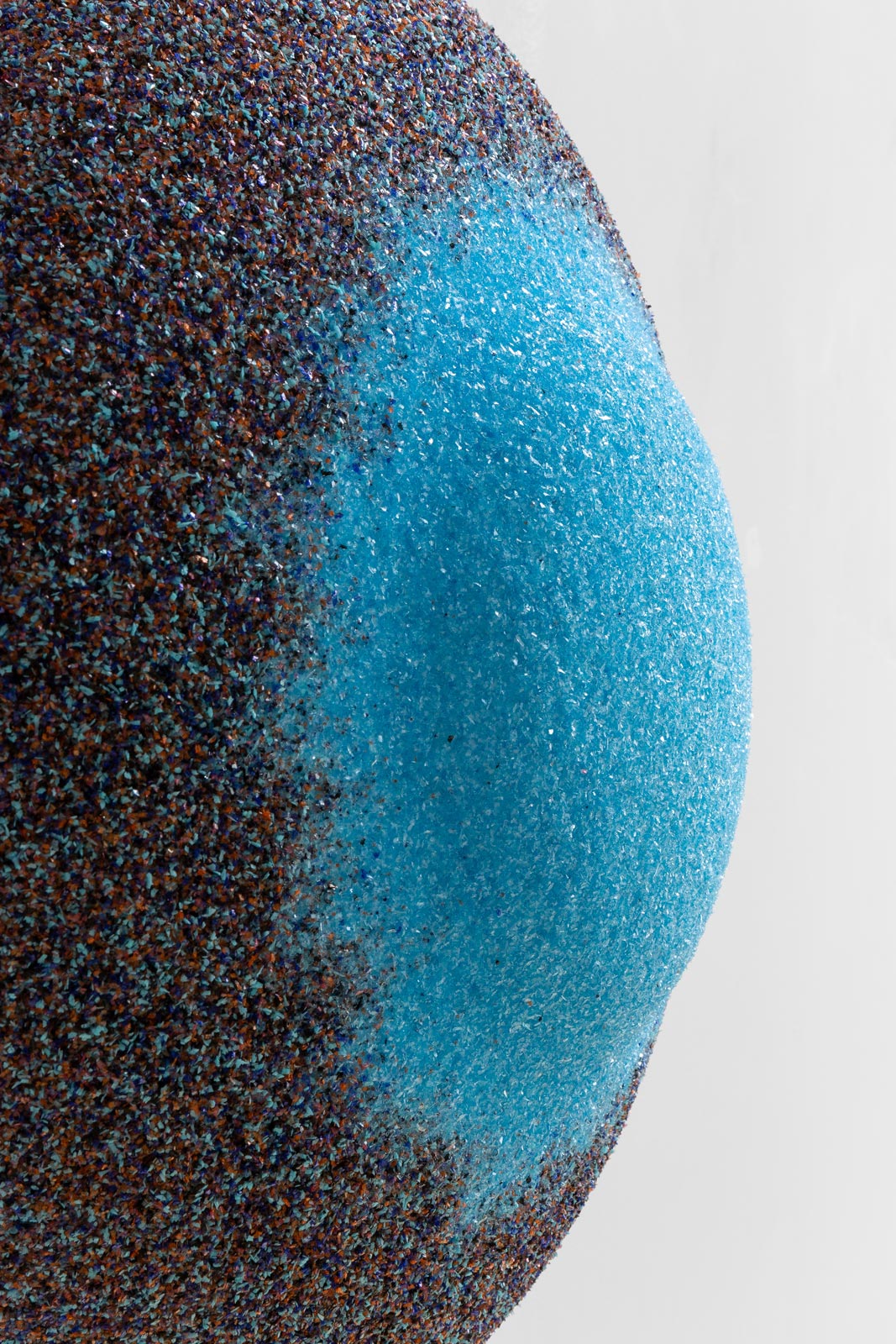

Polystyrene, glass.

Ř 55 x 24 cm

Unique

Polystyrene, glass.

Ř 55 x 24 cm

Unique

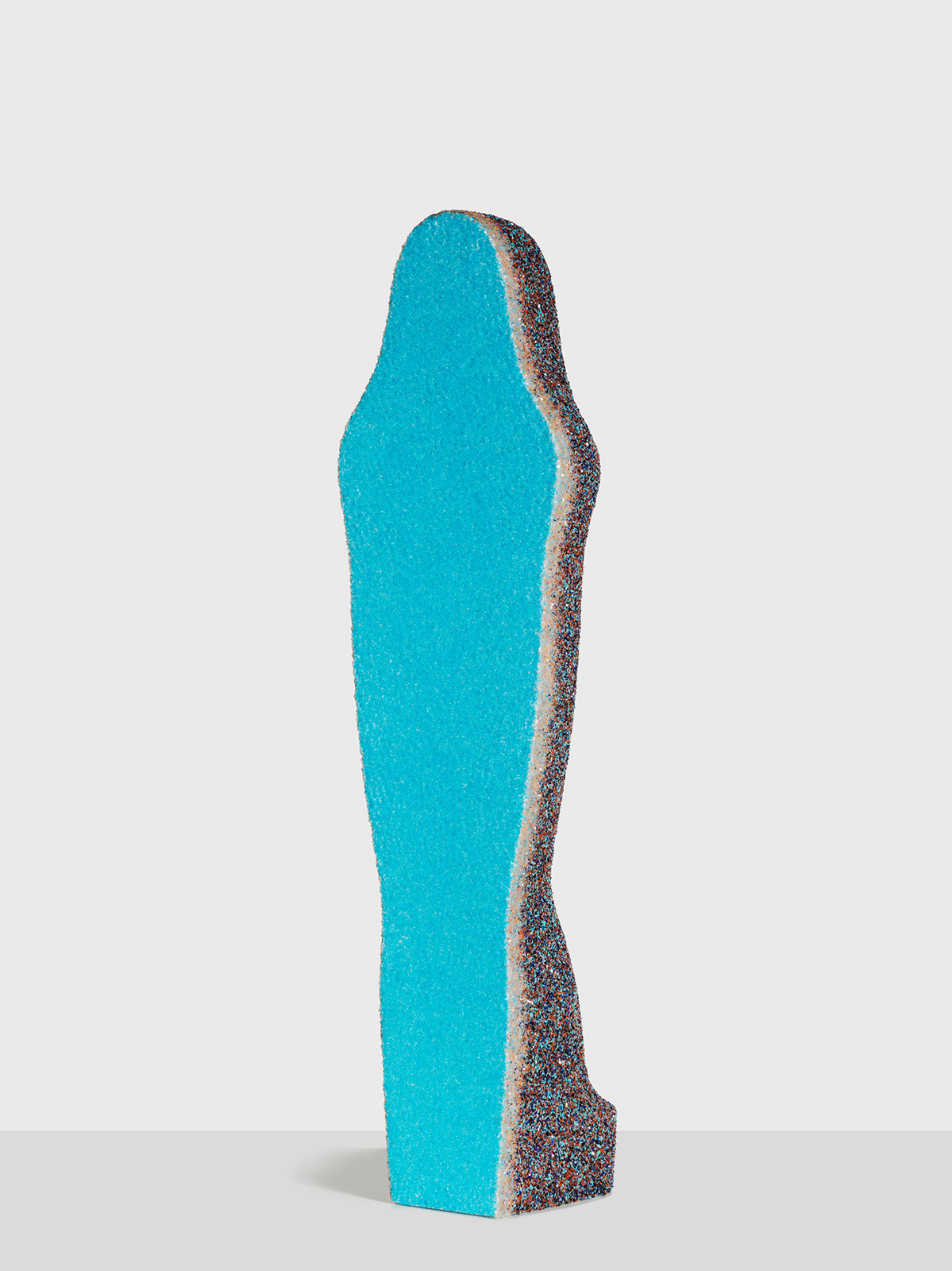

Polystyrene, epoxy resin, glass

82,5 x 24 x 22 cm

Unique

Polystyrene, epoxy resin, glass

82,5 x 24 x 22 cm

Unique

Polystyrene, epoxy resin, glass

Ř 71 x 13,5 cm / Ř 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique

Polystyrene, epoxy resin, glass

Ř 71 x 13,5 cm / Ř 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique

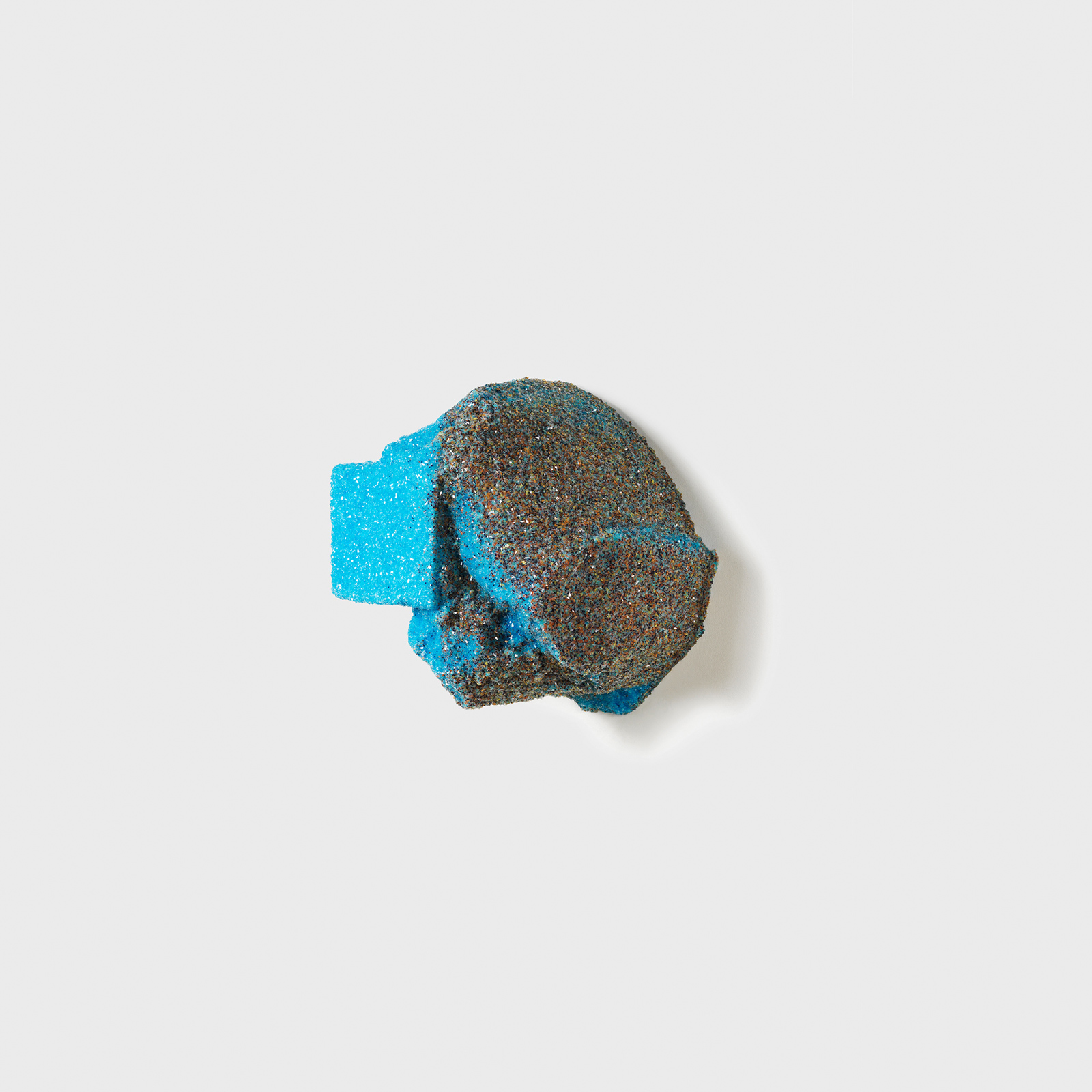

Polystyrene, glass.

22 x 28 x 15 cm

Unique

Polystyrene, glass.

22 x 28 x 15 cm

Unique

Polystyrene, epoxy resin, glass

Ř 71 x 13,5 cm / Ř 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique

Polystyrene, epoxy resin, glass

Ř 71 x 13,5 cm / Ř 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique

Polystyrene, epoxy resin, glass

Ř 71 x 13,5 cm / Ř 28 x 5 1/4 in.

Unique